Commercial Banks Cut Fixed Deposit Rates Further in Ashoj, Depositors’ Returns Under Growing Pressure

Author

NEPSE TRADING

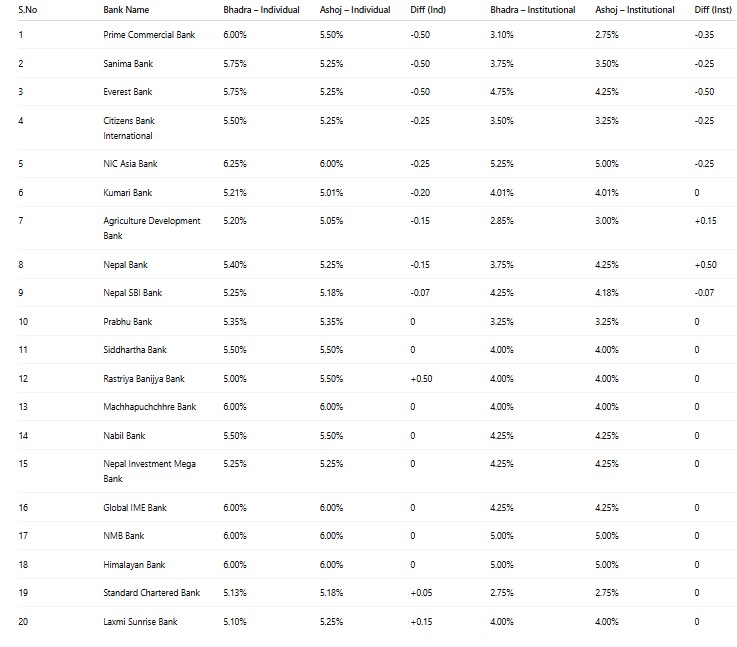

Kathmandu. All 20 commercial banks operating in Nepal have published their interest rates for Ashoj, and the figures show that fixed deposit rates have fallen further compared to Bhadra. According to the available data, the maximum average interest rate on individual fixed deposits dropped from 5.577% in Bhadra to 5.4635% in Ashoj, a decline of 0.1135 percentage points. This reduction directly affects the returns of small savers and ordinary depositors who rely on fixed deposits for steady income.

Out of 20 banks, 9 have slashed their individual fixed deposit rates in Ashoj. Prime Commercial, Sanima, Everest, Citizens, NIC Asia, Kumari, Agriculture Development, Nepal Bank, and Nepal SBI all lowered their rates. Some banks cut sharply by 0.50 percentage points, while others made smaller but meaningful reductions ranging from 0.07 to 0.25 points. This wave of reductions signals that banks are prioritizing “cheap deposits” rather than aggressively competing to attract funds.

Meanwhile, a few banks actually raised their rates. Data show that Laxmi Sunrise and Standard Chartered increased individual deposit rates by about 0.15 and 0.05 points respectively. Rastriya Banijya Bank also raised its rate by 0.50 points compared to Bhadra. The rest of the banks, such as Machhapuchchhre, Global IME, NMB, Himalayan, Nabil, and Nepal Investment Mega Bank, left their individual rates unchanged, keeping them steady around the 6% mark.

It is worth noting that some discrepancies may exist when cross-checking official notices, meaning final figures could differ slightly, but the overall downward trend is clear.

Institutional deposit rates also contracted in Ashoj. The maximum average institutional rate shrank by 0.0885 percentage points compared to Bhadra. This reduction directly impacts bulk depositors such as insurance companies, large corporations, and fund managers, cutting into their expected returns. While a few banks maintained institutional rates, the fact that many cuts mirrored those on individual deposits suggests that banks are focused on keeping the cost of wholesale funds under control.

The main reasons lie in the abundance of liquidity in the banking system and the sluggish demand for loans. Strong inflows of remittances have expanded the deposit base, but private sector investment has remained subdued, leaving credit growth weak.

This “more deposits, fewer loans” situation has reduced pressure on banks to offer high deposit rates. Instead, banks are carefully adjusting rates to balance their cost-income equation, ensuring that the average cost of funds aligns with the average earnings from loans.

The direct effect falls on depositors. A fixed deposit of one lakh rupees will now earn about Rs. 113 less annually because of the 0.1135 percentage point cut in average rates. For larger deposits, the effect increases proportionally.

Institutional investors also face the squeeze. A decline of 0.0885 points reduces expected income for insurance funds, pension/provident funds, and corporate treasuries, forcing them to reconsider their investment mixes to maintain target returns.

For borrowers, however, the trend is relatively positive. Base lending rates are closely tied to the cost of deposits. As deposit rates fall, base rates gradually decline over a few weeks to months, which could translate into cheaper loans—whether for housing, SMEs, or overdrafts.

Still, how much benefit actually reaches borrowers will depend on multiple factors: credit demand, risk assessments, regulatory conditions such as CCD and CRR/SLR, and each bank’s internal profitability targets.

Banks’ current strategies show differences.

Some large banks with strong retail deposit bases have kept maximum rates around 6% to protect their market share.

Others have opted for sharp cuts to reduce funding costs, anticipating weak lending growth in the near term.

A third group, including those bound by stricter international standards, raised rates slightly to send signals to specific customer segments or tenors.

Such divergence is natural in a competitive market, where each bank’s interest rate policy reflects its balance-sheet position and expectations about the future.

Analysts suggest depositors act more strategically: splitting funds across different maturities (“laddering”), checking the renewal terms carefully, and reading the fine print on which amounts and tenors actually qualify for “maximum rates.” Many banks apply their highest rates only for large deposits or limited periods.

Before switching banks, depositors should also weigh tax deductions (TDS), penalties for premature withdrawals, and potential counter-offers that banks might extend to retain clients.

In the short term, loan demand may temporarily rise during the festive season (Dashain–Tihar), which could tighten liquidity and slow the pace of falling deposit rates. But unless there is a sustainable revival in credit demand, the oversupply of deposits in the system will likely keep rates suppressed.

Over the longer term, only a strong push in productive lending—to businesses, industries, and infrastructure—can provide lasting upward pressure on deposit rates. Until then, depositors may face thinner returns, while borrowers enjoy cheaper credit.

The Ashoj rates confirm that Nepal’s banking system remains flush with liquidity. For depositors, shrinking returns are disappointing, but for borrowers, the outlook is moderately positive. The bigger question now is whether banks can go beyond just cutting costs and actively channel more loans into productive sectors, thereby stimulating broader economic growth. After all, the mathematics of interest rates is ultimately tied to the real economy of jobs, investment, and production.