By NEPSE TRADING

Nepal’s Export Boom: Soybean Oil Leads, But Fragile Structure Raises Red Flags

Nepal’s trade statistics for the first two months of fiscal year 2082/83 (mid-July to mid-September 2025) present a paradox. On the surface, the numbers appear highly encouraging. Exports surged by an astounding 88.57 percent, climbing to Rs. 47.31 billion from Rs. 25.09 billion in the same period of the previous fiscal year. This kind of growth, rarely seen in Nepal’s export history, immediately captured headlines and gave policymakers some room to celebrate.

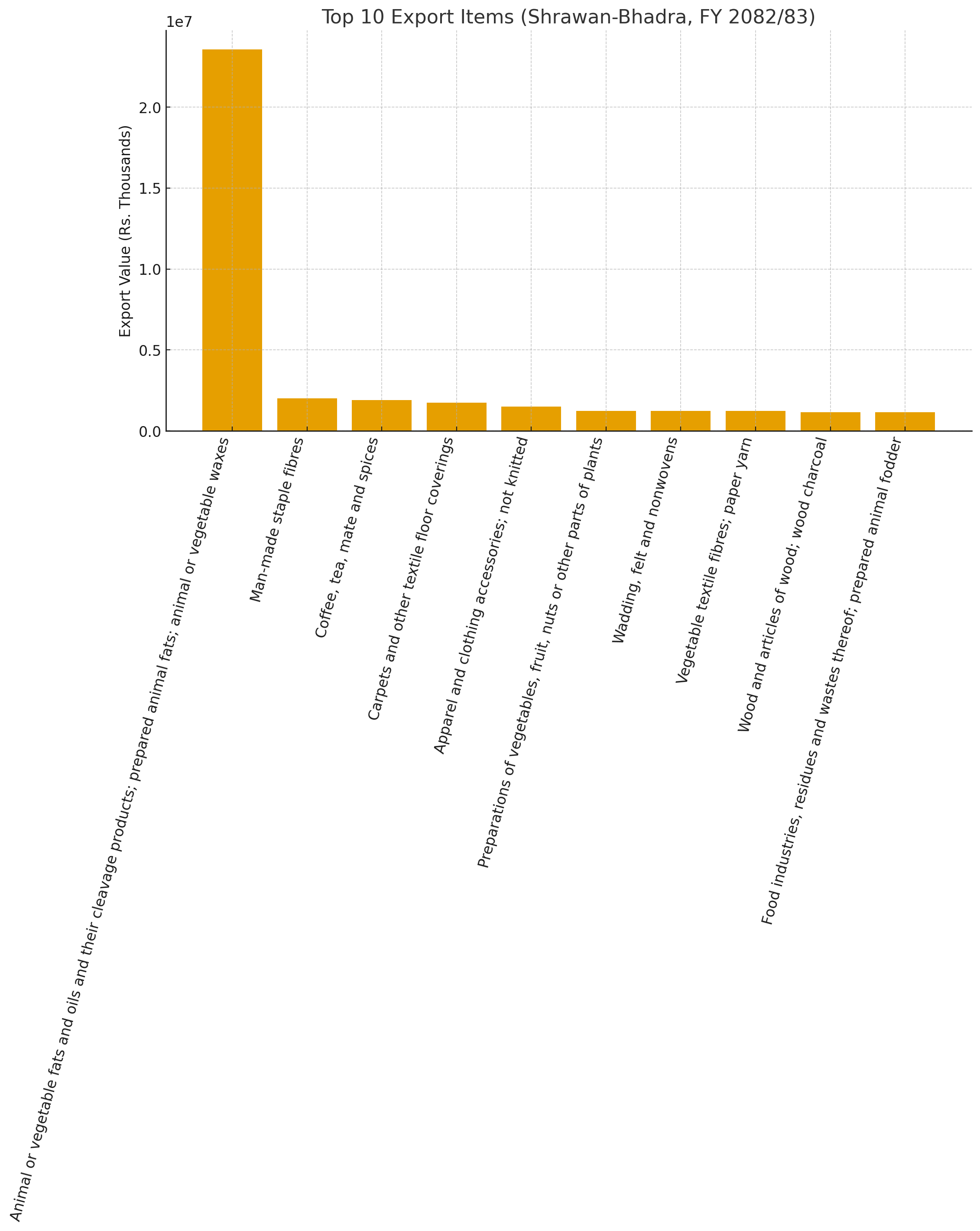

But a closer look at the structure of exports tells a different, more sobering story. The surge has been driven disproportionately by one commodity—soybean oil—which alone accounted for 56.84 percent of total exports. The rest of the basket, while diverse, still remains limited to traditional items such as tea, coffee, spices, textiles, garments, carpets, and wool. These goods, though significant, face constraints ranging from global competition to dependence on imported raw materials.

Thus, while the numbers shine brightly on paper, the underlying reality suggests that Nepal’s export engine is running on shaky foundations.

Soybean Oil: The Export Giant with Imported Roots

At the heart of Nepal’s export boom lies soybean oil. In just two months, Nepal exported nearly Rs. 20.42 billion worth of refined soybean oil, making it the single largest export item by a wide margin. The product’s overwhelming dominance is both a strength and a weakness.

On the positive side, soybean oil has given Nepal’s export sector a dramatic push. Without this single commodity, total exports would have remained modest, perhaps only marginally higher than last year. The product has opened access to foreign exchange earnings and contributed to industrial activity in certain regions where refining plants operate.

However, the weaknesses of this dependency are equally striking. Nepal does not grow soybeans in sufficient quantities to support such massive exports. Instead, industries import crude soybean oil from abroad—often from Argentina, Brazil, and other producers—and then refine and re-export it, mostly to India. This makes soybean oil exports more of a re-export activity than a homegrown success story.

Such a model creates several vulnerabilities:

Policy Risk – If India, the primary importer, changes tariff structures or imposes restrictions, Nepal’s export figures could collapse overnight.

Price Volatility – Global crude oil prices directly influence the cost of inputs, leaving Nepalese refiners at the mercy of international markets.

Lack of Value Addition – While refining adds some value, the broader economic benefits are limited. There is little forward or backward linkage with Nepal’s domestic agriculture.

Experts argue that relying on soybean oil is like “building a house on sand”—the foundation looks strong until external shocks wash it away.

Tea, Coffee, and Spices: Tradition Meets Opportunity

In contrast to soybean oil, Nepal’s exports of tea, coffee, and spices represent a more organic strength. Valued at Rs. 18.94 billion during the review period, these commodities form the second-largest export category. Unlike soybean oil, these are primarily Nepal-produced goods, cultivated in the fertile hills and plains, and increasingly recognized for their quality in international markets.

Ilam tea has long been considered a premium product, comparable in reputation to Darjeeling. Similarly, Nepalese ginger, cardamom, and pepper enjoy growing demand. These products are often described as “green gold,” offering potential for both smallholder farmers and large agribusinesses.

Yet challenges persist. While volumes are increasing, branding and global marketing remain underdeveloped. Nepal has yet to build strong geographical indication (GI) protections for Ilam tea, meaning that much of it gets re-exported under Indian branding. Moreover, post-harvest processing facilities are limited, reducing the ability to export higher-value packaged and branded goods.

Nonetheless, tea, coffee, and spices hold one of the brightest prospects for Nepal’s long-term export diversification. With investment in quality certification, organic branding, and trade diplomacy, these could gradually rival the dominance of soybean oil.

Textiles and Garments: The Old Guard Still Standing

The textile and garment sector has long been Nepal’s export backbone. In this two-month period, various sub-categories of textiles together contributed more than Rs. 56 billion in exports.

Breakdown of major segments:

Man-made staple fibers – Rs. 20.12 billion

Non-knitted apparel and clothing accessories – Rs. 14.95 billion

Knitted apparel – Rs. 9.18 billion

Vegetable textile fibers and yarn – Rs. 12.33 billion

Historically, garments were Nepal’s leading export, particularly to Western markets under preferential trade schemes such as the Multi-Fiber Arrangement. The industry suffered heavily when such schemes ended, leading to factory closures and job losses. The current figures suggest some resilience, but the industry still struggles with scale, technology, and competitiveness compared to Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Cambodia.

One key advantage Nepal retains is its relatively lower labor cost, but productivity and supply chain efficiency remain weak. To sustain growth, the sector requires targeted policy support, including investment in modern machinery, streamlined customs procedures, and new trade agreements.

Carpets and Wool Products: A Cultural Export Identity

Handmade carpets, valued at Rs. 17.33 billion, remain Nepal’s most recognizable cultural export. These products, often woven by artisans in Kathmandu Valley and surrounding regions, have long been admired in European markets for their craftsmanship and quality. Similarly, woolen products and yarn continue to form a niche segment of Nepal’s exports.

The challenge, however, is generational. Younger Nepalis are less inclined to pursue carpet weaving as a livelihood, seeing it as labor-intensive and low-income. As a result, sustaining this traditional export sector requires both modernization and re-branding. Eco-friendly dyes, fair-trade certification, and luxury marketing could help revive carpets as a premium product in global markets.

Processed Foods and Wood Products: Emerging Contributors

Beyond the traditional sectors, exports of prepared foods and animal feed (Rs. 11.44 billion) and wood and wooden products (Rs. 11.55 billion) also made it into the top 10. These reflect the gradual emergence of smaller industries finding niches abroad.

Processed foods, in particular, show promise. With rising demand for ready-to-eat items in South Asia and the Middle East, Nepal could expand this category significantly. Similarly, wooden products—though often criticized for potential links to deforestation—can generate value if managed through sustainable forestry practices.

The Bigger Picture: Impressive Growth, Fragile Structure

When combined, the top 10 export items account for nearly the entire export basket, revealing how narrow Nepal’s export base remains. The reliance on a few products—especially soybean oil—makes the growth unsustainable in the long run.

Several structural issues stand out:

Over-concentration – More than half of exports depend on one product.

Import Dependency – Many exports, like soybean oil and garments, rely heavily on imported raw materials.

Low Value Addition – Nepal’s exports often represent the lower end of global value chains, missing out on branding and innovation.

Market Dependence – India remains the primary buyer for most categories, creating risks if bilateral trade relations sour.

Expert Opinions and Policy Implications

Economists highlight three major areas Nepal must address:

Diversification – Move beyond soybean oil and garments by developing new sectors such as IT services, high-value agriculture, tourism services, and hydropower trade.

Value Addition – Invest in processing, branding, and innovation so that Nepal is not just exporting raw or semi-processed goods.

Market Expansion – Secure preferential access to developed economies, particularly Europe and East Asia, through trade agreements.

Without such strategies, Nepal risks repeating a cycle of export booms followed by sudden crashes whenever one dominant product loses competitiveness.

The first two months of FY 2082/83 have shown what Nepal is capable of achieving in export growth, but also what it risks by failing to diversify. The soybean oil boom is a short-term blessing but a long-term risk. Traditional sectors like tea, coffee, spices, and carpets offer resilience but require modernization. Emerging sectors like processed foods and wood products show potential but remain small.

Nepal’s export story today is one of promise wrapped in fragility. The challenge for policymakers is to turn this moment of growth into a foundation for sustainable, diversified, and resilient trade.